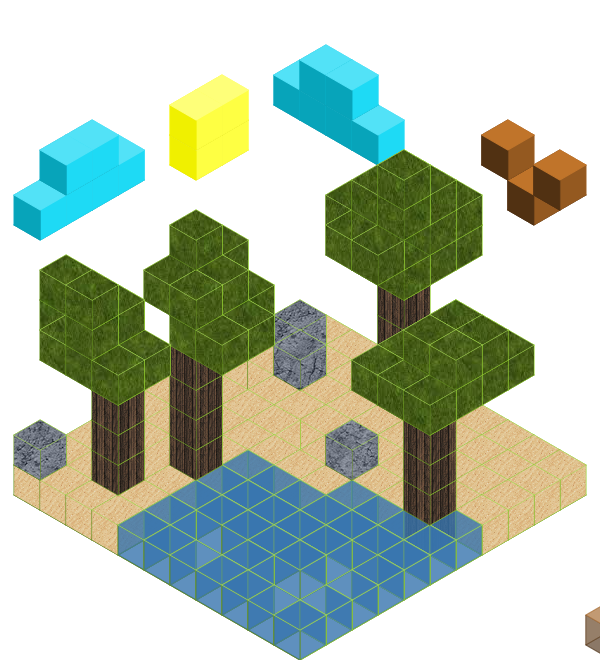

The story of Bloc: An isometric, multiplayer building game

The image of something approximating the lovechild of Lego and Minecraft suddenly popped into my head and before I knew it I had volunteered “An isometric, multiplayer building game!” to our final project brainstorming session - and so team Bloc was born!

Platform & technology

After discussing our visions of the game (which it turned out were remarkably similar) we set about exploring the pros and cons of different platforms and relevant technology stacks. We quickly established three options: mobile (java/objective C), Unity (C#/javascript) or the browser (javascript). Given our deadline and the overhead of learning a new language to build an app natively for mobile, we opted for the browser, leaving us the option to package our app for mobile with a platform like PhoneGap later.

The next stage was deciding which (if any) libraries to use. Some of the team (myself included) had worked together building a game for a prior project (playable here) where we decided not to use any libraries in favour of tackling the technical challenges (collision detection, game loop/draw loop et al). Envisaging plenty of technical challenges associated with our 2.5D perspective regardless of the library choice, we settled on using a javascript library to handle the basic drawing of our shapes. After experimenting with both Isomer.js and Obelisk.js, we chose Isomer given the approachability of its documentation and perceived wider adoption amongst the coding community.

See our GitHub readme for a full list of the technologies used.

MVP

Our MVP was written as pure client side javascript (based on our previous experience) with an MVC pattern. Taking our coaches advise to make our MVP the crappiest (sic) version of the game possible, we decided on a single user story:

“As a game So that I can exist I want to display a block on a canvas in the browser”

Awesome! We spiked the MVP given how unfamiliar we were with using the canvas and the Isomer library.

Version 2 & Testing

With our block in place, we set about our next group of user stories but quickly hit a hurdle; as we discussed the structure of the application, we struggled to visualise where each part of the code should live. We used our diagramming skills to illustrate the intended message flow for placing a shape in our game, from client to server and back again. This led to a realisation that our game (reality) should be on the server, not the client. Each client browser should merely send instructions to the game and receive updates when the world changes to represent the current state of play. We also explored the concept of the skinny client. And so we set about moving our game onto the server.

We had all expressed an interest in experimenting with javascript frameworks and taking our javascript further, so plumped for Node.js. Having used jasmine 2.0 on the client side in previous projects, we initially talked about using jasmine CLI to TDD the game but quickly switched to use Mocha, Chai and Sinon after realising jasmine CLI currently only supports jasmine 1.3 (older syntax) and following advice from earlier cohorts.

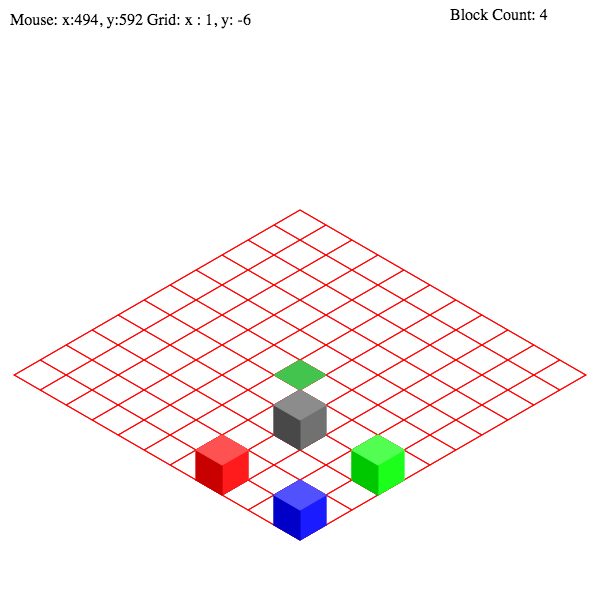

To achieve version 2, our basic requirements were to have the game delivered from a server and have a single Shape class. We set-up a basic express app inside the game and served a single route (‘/’) over localhost. We TDDed a Shape class with some basic properties (x, y, z position). Leveraging the grid position system of the library we used to draw a shape, we were able to quickly draw multiple shapes.

Version 3 & web sockets

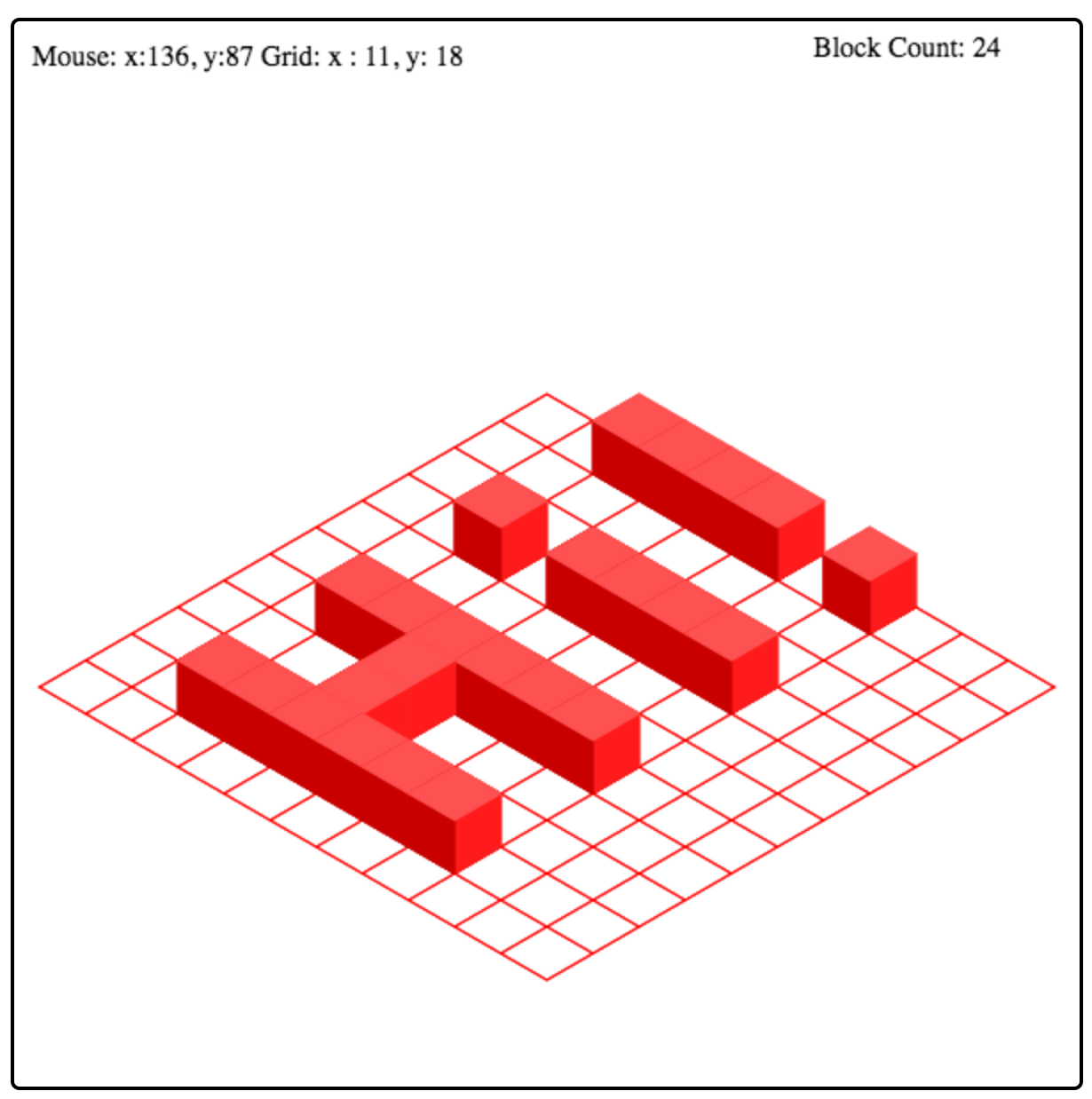

And then came maths! We dedicated a lot of time to solving a number of issues, core to the manipulation of our game world including rotation, converting mouse position into cartesian coordinates on our isometric grid and most importantly the fall-out from these operations! One example of the butterfly effect was the draw order of shapes on the canvas; shapes must be draw from back to front on the X-Y axis and bottom to top on the Z axis to satisfy the top down camera view. We initially coded rotation on the server but feature testing highlighted how frustrating it was to have another player rotate the world as you were trying to place a block! Moving this code away from the server also made sense in terms of where the game ‘reality’ lives; our server rotation thus far would alter the actual coordinates of each block in the game; rather than rendering the player’s perception, the whole game was being modified. The solution was to move rotation to the client, along with shape sorting.

We also tackled the multiplayer element of the game for version 3, introducing web sockets to the project using the socket.io library. While this helped us to better structure the code base, it introduced a layer of complexity for testing that we didn’t manage to overcome before the project deadline.

Version 4 and a mad dash for the finish line

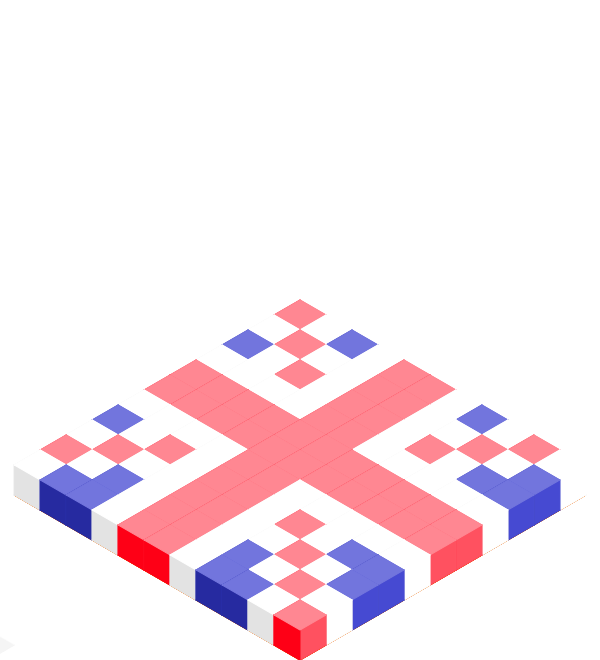

With a feature freeze looming on second Tuesday of our two-week build, we fell into an obvious (with hindsight) trap, cramming as many shiny new features into the game as possible; we were trying to fit a stereo to our skateboard! I think we felt a weight of expectation to produce something tangible given we were building a game and this ultimately impacted our code quality given the deadline. From textured shapes to individual game rooms, MongoDB and Facebook login, we managed to implement lots of impressive features but come refactor time may have created a rod for our own back.

We regularly fought the urge to use a shiny and sophisticated UI framework (such as React); it always felt like using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut given the relatively slow refresh we needed and our use of the canvas. We decided to use jQuery to update the DOM and redraw the whole canvas each time the game updated. With hindsight, this added complexity to our client javascript DOM manipulation but saved us a fundamental rewrite of the server code mid-way through the project.

Bloc was released to a broad audience comprising two other Makers cohorts on graduation day. While the Heroku server held up under load, bugs inevitably appeared, mostly relating to a lack of error catching - we had a lot of fun fixing them in real-time!

Improvements

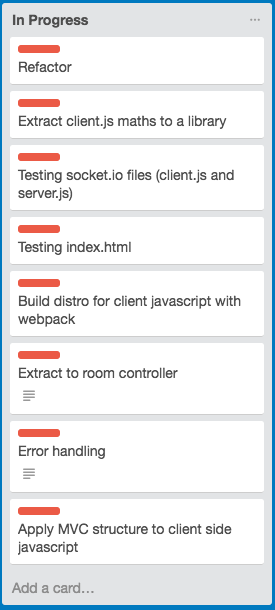

Plenty! At the time of writing, we have eight ‘in-progress’ cards on the project Trello board which we are working to address over the next few weeks:

In the meantime, Bloc is live and playable at https://bloc-game.herokuapp.com so get building!

The source code (currently being refactored) is available at https://github.com/joemaidman/bloc

Demo video

Bloc was built by Sophie Mclean, Christos Paraskeva, Ryan Chu and Joe Maidman as a final project for the February 2017 cohort at Makers Academy.